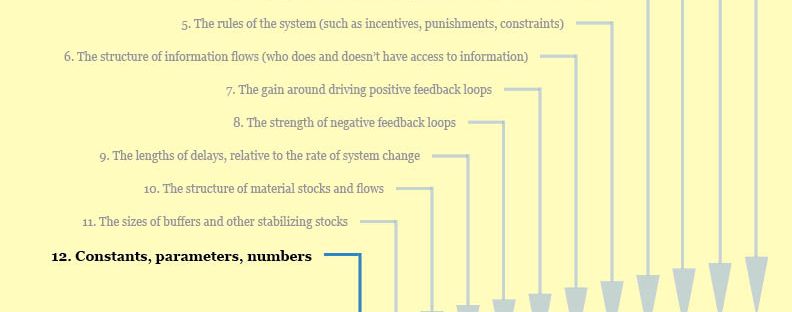

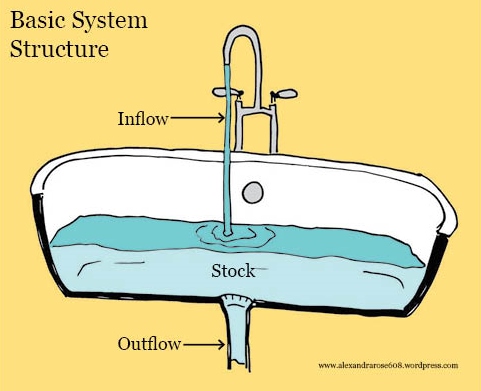

We’re going to start off our system leverage point bonanza with the point described by Donella meadows as having the lowest potential impact: numbers, constants, and parameters such as subsidies, taxes, and standards. But first let’s review basic system structure. Enter the bathtub diagram!

Every system is made up of inflows, outflows and a stock. From Ms. Meadows’ Thinking in Systems,

Every system is made up of inflows, outflows and a stock. From Ms. Meadows’ Thinking in Systems,

“A stock is the foundation of the system. Stocks are the elements of a system that you can see, feel, count, or measure at any given time. A system stock is just what is sounds like: a store, a quantity, an accumulation of material or information that has built up over time. It may be the water in a bathtub, a population, the books in a bookstore, the wood in a tree, the money in a bank, your own self-confidence….Stocks change over time through the actions of a flow. Flows are filling and draining, births and deaths, purchases and sales, growth and decay, deposits and withdrawals, successes and failures.”

So, the leverage point concerning numbers is fiddling with the stock, how much or how little water we want in the bathtub. Perhaps because stocks are commonly the most tangible elements in a system people really like to mess with them despite the fact that this strategy rarely has lasting or impactful results.

Consider our propensity for designing recycling programs, for example. In this case, the stock would be the amount of material getting recycled. In and of itself, recycling is not a bad thing. It raises awareness about environmental concerns and keeps an amount of material out of landfills or, um, waterfills. Recycling is a great transitional strategy on the road to a sustainable culture but not an end in itself. Ideally, recycling wouldn’t be necessary because the small amount of products we used would be part of a closed loop system wherein material quality is not lost. Except for some types of plastic, recycling reduces material quality much in the same way we breakdown and simplify natural materials to make new products. Paper, for example, can only be recycled about five times before its fibers lose the structural integrity necessary for a new sheet.

In fact, the most optimal recycling systems may actually have negative impacts on the environment due to single action bias and moral licensing. This is thinking, “I can continue to consume products as quickly as I want because I recycle all of my packaging.” Or, “I’m the best recycler on the block so I’ve earned the right to take twenty minute showers.” When it’s one of a limited number of environmental strategies, it also sends the message that product waste headed to landfills is one of the more harmful parts of our environmental footprint, which climate change scientists would tell you is not the case.

Ultimately, the amount we recycle does very little or nothing to change to system of consumption itself. Widgets keep being made and we can’t wait to buy them.

There are exceptions to the effectiveness of this leverage point, however. As Meadows states,

“Parameters become leverage points when they go into ranges that kick off one of the items higher on the list…These kinds of numbers are not nearly as common as people seem to think they are. Most systems have evolved or are designed to stay far out of range of critical parameters. Mostly, the numbers are not worth the sweat put into them.“